Immigration History

Image Source: Independence Hall of Korea.

The first Hawaiian immigrants arrived in Honolulu at dawn on January 13, 1903, on board the Gallic.

Korean immigration to the United States began at the end of the Joseon Dynasty in the mid-1800s with the arrival of individual merchants, students, and adventurers. Korean immigration officially began in 1903 when RMS Gaelic brought 102 Korean contract workers to work in sugar cane plantations in Hawaii.

By 1905, more than 7,000 Korean immigrants had stepped on the shores of Hawaii. While most of the immigrants were men, from 1910 to 1924, Korean women were also part of the migration as wives of plantation workers. Some of the Korean plantation workers migrated to the mainland of the United States after the expiration of their labor contracts and joined other Korean immigrants to form Korean communities and settlements from California to New York.

Image Source: The Korean National Association Memorial Foundation.

On April 17, 1938, an opening ceremony was held for the newly built General Assembly Building of the Korean National Association.

On February 1, 1909, the San Francisco Mutual Assistance Society and the United Korean Society of Hawaii merged to form the National Association, a unified organization of Koreans in the United States. Then in 1910, the National Association merged with the Great East Patriotic Association and was renamed the Korean National Association. To restore Korea’s national sovereignty and rebuild as an independent country, they established 116 local councils throughout five regional branches in North America (including Mexico), Hawaii, Manchuria, and Siberia.

In 1913, the Korean National Association was recognized as a representative organization of Korean Americans by the U.S. Secretary of State when the Korean National Association took a governmental role and negotiated with the U.S. Department of Commerce to allow entry to Koreans with a Korean National Association certificate instead of a passport.

Image Source: Independence Hall of Korea.

This is the image of people cheering along with independence activists who were released from Mapo Prison right after liberation in 1945.

The defeat of Japan and the end of World War II put Korea on the path to independence. Koreans throughout the world rejoiced the end of Japanese rule.

Image Source: National Archives & Resource Administration, USA.

On July 6, 1950, U.S. ground forces committed to the Korean War arrived at a port in Korea.

The Korean War began when North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. The bitter war lasted for three years until an armistice ended the fighting on July 27, 1953.

One of the outcomes of the Korean War was the immigration of approximately 6,000 Korean women who arrived in America as wives of U.S. servicemen. Additionally, war orphans and children of American soldiers who were left behind faced tremendous hardship in Korea. International adoption of these children began with the U.S.-based Holt International Children’s Services and expanded with the active coordination of the Korean government’s Overseas Adoption Project. These groups represent an important portion of Korean immigrants.

Image Source: Wikipedia

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the bill into law as Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Senators Edward M. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy and others look on.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarren-Walter Act

This act allowed people of all races to immigrate to the United States. For the first time, the U.S. government granted an immigration quota of 100 per year to South Korea. However, the act still maintained the national origins system that imposed a quota system to restrict non-European immigration. Additionally, the act allowed all immigrants-regardless of race-to become naturalized citizens of the United States. Until this act, Korean immigrants could not legally become U.S. citizens.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 19652 (The Hart-Celler Act

This Act finally abolished the racially discriminatory national origins system. All nations were granted equal quotas for immigration, and the Act opened the door to family- and employment-based immigration. The act emphasized family reunification and skilled workers and also created non-quota category of immigrants that included spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens.

As a result of this immigration policy, immigration patterns in the United States have changed dramatically, with the rapid increase in the numbers of Asian and Latin American immigrants. The number of Korean immigrants also increased due to special immigration visa programs, including programs for nurses and doctors.

Image Source: Sundance Film Festival.

Free Chol Sool Lee (Documentary)

“Free Chol Soo Lee” was a social movement for the release of Lee, who was framed and wrongfully convicted of murdering Yip Yee Tak, an alleged San Francisco Chinatown gang member in 1973. This movement that lasted a decade is often cited as an example of the Asian American civil rights movement in the United States.

This case drew attention as a result of relentless investigative reporting by the influential Korean American journalist K.W. (Kyung-won) Lee. After the media publicized the case, the Korean American community, along with other Asian American communities, gathered in an effort to retry the case. The resulting Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee led the effort to overturn the original conviction, and Lee finally was freed from prison on March 28, 1983.

Image Source: Wikipedia

11/6/1986 President Reagan in the Roosevelt Room signing S. 1200 Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 with Dan Lungren Strom Thurmond George Bush Romano Mazzoli and Alan Simpson looking on

Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 was championed by President Ronald Reagan. The Act allowed undocumented immigrants who entered the country before January 1, 1982, to apply for legal status. Three million undocumented immigrants obtained permanent residency through this law, including many Koreans. In an effort to discourage undocumented immigration, the Act also emphasized strict enforcement with provisions to punish employers who knowingly hire undocumented immigrants.

Image Source: Wikipedia.

Burned buildings in Los Angeles

On March 3, 1991, four Los Angeles police officers brutally beat Rodney King, an African American motorist. Their acquittal a year later, in 1992, prompted one of the worst race riots in American history. After the acquittal, protesters, who were in shock and anger, engaged in massive political protest that included widespread looting and arson. During four days of civil unrest, over 50 people were killed, 2,000 were arrested, and property damage totaled more than $1 Billion. African Americans represented the majority of those killed, Latinos represented the majority of those arrested, and Korean Americans alone sustained 40 percent of the economic damage.

As riots intensified, the existing tension between Korean Americans and African Americans worsened. The Soon Ja Du Incident of 1991 (the killing of Latasha Harlins, an African American girl, by Du, a Korean American storeowner) and the media’s coverage of the criminal trial that resulted in Judge Joyce Karlin’s light sentence for Du’s conviction for voluntary manslaughter stoked the resentment of some African American activists and residents toward Korean Americans and their businesses in South Los Angeles.

Koreatown’s location, between the affluent white areas of Hancock Park and Miracle Mile and the impoverished African American and Latino neighborhoods of South Central and Pico-Union, was left unprotected by the Los Angeles Police Department and led to devastation. As some Korean Americans armed themselves due to the absence of police, the mainstream media portrayed them as vigilantes.

During this time, Angela Oh and other second-generation Korean Americans spoke out through the mainstream media and ushered in a generational shift in Korean American

community leadership. This event also launched a long movement for political mobilization that led to election of Korean American political leaders from Los Angeles City Hall to the U.S. House of Representatives.

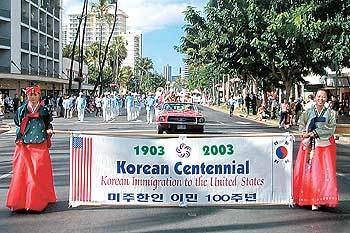

Image Source: The Christian Herald USA.

The celebration of the 100th anniversary of Korean immigrants to the United States opened in Hawaii with a large-scale parade.

Citing the arrival of the first group of Korean workers to Hawaii, President George W. Bush officially declared January 13, 2003 as the 100th anniversary of Korean immigration. The 100th anniversary project started in Hawaii and various commemorative events were held throughout the United States with the support of the Korean government.

The 100th anniversary served to build momentum to celebrate and publicize Korean American history and inspire Korean American pride. It also promoted friendship between Korea and the United States, as many cities and local governments began proclaiming and celebrating the ‘Korean American Day’ on January 13th of each year.

Image Source: Cultural Heritage Administration, Korea.

The Hunminjeongeum Haeryebon is National Treasure No. 70 and a UNESCO Memory of the World Register. It explains in detail the principles and usage of consonants and vowels in Hangeul.

On September 9, 2019, The California State Legislature unanimously passed a bill designating “Hangul Day” to recognize the Korean American community’s contribution to the state. This is the first Hangeul anniversary established overseas and the first minority language anniversary in the United States.

Source: Korean Education Center in L.A (Korean Immigration History Museum)