Economic Development and Democratization of South Korea

Seoul at Night

To anyone who is familiar with Korean[1] popular culture, electronics, or automobiles, South Korea is an obvious economic success, deserving of the nickname “The Miracle on the Han” (the river that runs through the capital city of Seoul)[2] . This rise to become one of the largest economies in the world[3] is even more remarkable given Korea’s recent history of Japanese colonization (1910-1945)[4] and the Korean War (1950-1953)[5], both of which left deep scars across the peninsula. Additionally, after years of authoritarian rule, South Korea democratized in 1987 and has continued to improve, ranking 24th among nations that have a “full democracy,” according to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2022[6]. Today, South Korea is a model of economic success and democratization for countries hoping to achieve the same. In this reading, we will discuss South Korea’s postwar economic and political journey, and see how this success did not happen overnight, but was achieved through blood, sweat, and tears.

- 1.The terms Korea/Korean are often used interchangeably to mean South Korea/South Korean.

- 2.This nickname was borrowed from West Germany being called “Miracle on the Rhine” after WW2.

- 3.There are many different ways of calculating economic size and rank, and South Korea reclaimed the 10th spot in 2021 when measuring 2020 nominal GDP of $1.63 trillion. See Hankyoreh, “S. Korea Now Ranks World’s 10th Biggest Economy,” (April 22, 2021), https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_business/992192.html, accessed December 12, 2021. Due to global and domestic economic concerns as well as currency exchange rates, Korea is expected to take 12th place among G20 countries for 2022 GDP, according to OECD estimates. See Kim Yon-se, “Korea to Rank 12th among G-20 Nations in 2022 Growth: OECD,” The Korea Herald (September 26, 2022), https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220926000750, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 4. Korea’s mythical founding of Old Joseon dates back to 2,333 BCE, but recorded history is scant from the early proto-states period. We can, however, trace the founding of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla (collectively known as the Three Kingdoms) to the 1st century BCE. Silla defeated its neighbors in the unification wars in the 7th century, and then fell to Goryeo in 935, which in turn was defeated by Joseon in 1392. When Korea was colonized by Japan in 1910, Koreans lost their sovereignty but held on to their long history and culture.

- 5.The Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950 and an armistice (ceasefire) agreement was signed on July 27, 1953 but no peace treaty has been signed, so the war has not yet officially ended.

- 6. For comparison the United States ranked 30th and was categorized as a “flawed democracy.” Korea had reached 16th on the index in 2021. See The Economist, “The World’s Most, and Least, Democratic Countries in 2022,” (February 1, 2023), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/02/01/the-worlds-most-and-least-democratic-countries-in-2022, accessed February 20, 2023.

| August 1948 | Establishment of the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea |

| April 1960 | Student Revolution leads to the resignation of Syngman Rhee and ushering in of the Second Republic headed by Premier Chang Myon. |

| May 1961 | Coup by Park Chung-hee |

| November 1972 | Yushin Constitution ending direct elections and giving the sitting president increased authority |

| October 1979 | Assassination of Park Chung-hee, ending 18 years of dictatorship |

| December 1979 | Coup by Chun Doo-hwan |

| May 1980 | Gwangju Uprising |

| June 1987 | June Democratic Struggle resulting in resumption of direct elections, greater civil rights |

| December 1992 | Election of Kim Young-sam, first civilian president in almost 30 years |

| Sept-Oct 1988 | Korea hosts the Seoul Olympics |

| December 1997 | Election of Kim Dae-jung, longtime dissident |

| June 2021 | Korea attends the G7 Summit in recognition of its economic and democratic strength |

| 1950-1953 | Korean War |

| 1964 | First Five-Year Plan for economic development |

| 1965 | Treaty on Basic Relations between Korea and Japan |

| 1966 | Brown Memorandum bringing South Korea into the Vietnam War as a US ally |

| 1968 | Founding of POSCO (Pohang Iron and Steel Company) |

| 1970 | GNI per capita is about $225[7] |

| 1972 | Founding of Hyundai Shipbuilding |

| 1976 | Hyundai launches the Pony, the first Korean passenger car |

| 1980 | GNI per capita is about $1.660 |

| 1988 | Korea hosts the Seoul Olympics |

| 1990 | GNI per capita is about $6.303 |

| 1996 | Korea joins the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| 1999 | Coining of the term Hallyu (Korean Wave) |

| 2000 | GNI per capita is about $11,292 |

| 2018 | Korea hosts the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics |

| 2020 | GNI per capita is about $31,881 |

When Japanese colonialism and World War II ended on August 15, 1945, Korea became divided at the 38th Parallel and was jointly occupied by the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the north. The Soviets withdrew in 1947 the Americans in 1948. Unable to form a single country, Koreans formed the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) but the early years of these newly established countries were marked by much turmoil.

After about a year of tensions and border skirmishes between the two Koreas, the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950 when North Korean troops crossed the border. North Korean forces, known as the Korean People’s Army, were armed with Soviet equipment and had combat experience from the Chinese civil war. They captured Seoul in two days and continued to push the Republic of Korea Army southward until only an area known as the Busan (or Pusan) Perimeter remained under South Korean control. The United Nations came to South Korea’s aid and American troops landed at Incheon on September 15, cutting off North Korean supply routes, forcing a North Korean retreat. UN and ROK troops regained South Korea and pushed north, capturing most of North Korea. The People’s Republic of China sent troops to aid North Korea, leading to a retreat of UN and ROK forces. All this happened in the first six months of war. The war raged on over the next two and half years, and by July 1953, took the lives of hundreds of thousands of soldiers from the Two Koreas as well as other countries,[8] and millions of Korean civilians from both north and south.

- 8.The terms Korea/Korean are often used interchangeably to mean South Korea/South Korean.

South Korea is said to have lost almost half of its industrial capacity, one-third of its housing, as well as much of its infrastructure during the Korean War.[9] Therefore, South Korea’s primary concern was economic recovery and anti-communism. American economic assistance was also grounded in bolstering capitalism as a defense against communism, and within South Korea, authoritarian rule was justified in the name of economic growth and anti-communist vigilance throughout the Cold War.

President Syngman Rhee (1875-1965, president 1948-1960) had held onto power by eliminating term limits, rigging elections, and using the National Security Law to go after political opponents and repress political freedoms. In the aftermath of election irregularities and police brutality, some 30,000 students took to the streets to protest on April 19, 1960 and 130 protestors were killed and another 1,000 injured by police. This came to be known as the 1960 Student Revolution and ushered in a new era of democracy. But those efforts failed when Park Chung-hee (1919-1979, in power 1961-1979) staged a coup d’etat in May 1961 and controlled the government through a junta until he officially stepped down in 1963 to run for president as a civilian.

Park Chung-hee created the Economic Planning Board to direct economic growth through control of the banking system, providing low-interest loans to businesses according to Five-Year Development Plans. Additionally, the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Korea and Japan (also known as the 1965 ROK-Japan Normalization Treaty) brought in $800 million[10] in aid and loans to Korea. In 1966, Park signed the Brown Memorandum and brought South Korea into the Vietnam War as a US ally, receiving $1 billion for direct support for some 50,000 soldiers, including “overseas allowances, arms, equipment and rations” as well as “modernization of South Korean forces in their own country, procurement of military goods in South Korea for United States forces in South Vietnam, expanded work for South Korean contractors in South Vietnam, and financial aid.”[11] These two actions gave Park the funds for South Korea’s export-oriented industrialization and technology acquisition, with government support to start companies like the Pohang Iron and Steel Company (POSCO, founded 1968) and Hyundai Shipbuilding (founded 1972). Additionally, Pyeonghwa Market (established 1962) and Guro Industrial Complex (established 1967) housed thousands of factories in which workers toiled for low wages in often dangerous conditions. Although there were many attempts by workers to unionize and workers staged strikes, labor rights were suppressed, often violently and in the name of economic development and anti-communism. From 1970, Park also pushed for rural revitalization through the Saemaeul (New Village) Movement.[12] Thousands of Korean miners and nurses also went to West Germany and many others emigrated to other countries as well.

Figure 1: Gyeongbu (Seoul-Busan) Expressway

Source: Korea.net[13]

Chun’s economic development plans were similar to those of Park, with Korea ranking high among the world’s top steel exporters and shipbuilders. South Korea also shifted from labor-intensive goods such as textiles to high-tech products like electronics, computers, semi-conductors, and automobiles. Korean construction firms also won many large-scale building projects in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. But there was continued suppression of labor rights with a strict crackdown on worker-led unionization and strikes. After the Gwangju Uprising, there were continued calls for democratization throughout Chun Doo-hwan’s regime, with a coalition of students, labor, religious institutions, women’s groups, and middle-class Koreans joining in together in mass protests in Seoul and elsewhere. Their efforts culminated in the June Democratization Struggle of 1987 and the resumption of direct presidential elections by popular vote for the first time since 1971. As seen in the April 1960 Student Revolution and throughout the 1980s as well, students played an important role in South Korea’s democratization process.

- 9.Carter Eckert, Ki-baik Lee, Young Ick Lew, Michael Robinson, and Edward W. Wagner, Korea Old and New: A History (Seoul: Ilchokak Publishers for Korea Institute, Harvard University, 1991), 345.

- 10.All monetary amounts are given in US dollars.

- 11.Richard Halloran, “Korea’s Vietnam Troops Cost U.S. $1 Billion,” The New York Times (September 13, 1970), https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/koreas-vietnam-troops-cost-us-1billion.html, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 12.Kyung Moon Hwang describes the Saemaeul Movement as “comprehensive, driven by a systematic, large bureaucracy that directed money, labor, and expertise to mechanization, irrigation, road construction, electricity, and the provision of consumer items.” See Kyung Moon Hwang, A History of Korea, 3rd ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 197.

- 13.Korea.net, “Transition to a Democracy and Transformation into an Economic Powerhouse,” https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/History/Transition-Democracy-Transformation-Economic-Powerhouse, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 14.Official data from Lee Tae-hoon, “Gwangju Movement Bitter Turning Point for Democracy,” The Korea Times, May 17, 2010, https://koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2010/05/113_66017.html?utm_source=gonw, accessed February 24, 2023. For more info, see The May 18 Memorial Foundation, http://eng.518.org.

Although Chun’s handpicked successor, Roh Tae-woo (1932-2021, president 1988-1993), won the 1987 election over an opposition that was split among three candidates, South Korea’s achievement of democratization was still monumental. With the world’s attention on Korea in the months leading to the 1988 Seoul Olympics, the government made good on its promises to strengthen civil rights. Five years later, Kim Young-sam (1927-2015, president 1993-1998) won the 1992 presidential election, marking the election of the first truly civilian president in many years. Under his administration, former presidents Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo were brought to trial and found guilty of charges relating to the 1979 coup. South Korea joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1996, signifying its economic success and the first time that a former aid-recipient joined the Development Assistance Committee as a donor.

In 1997, opposition party leader Kim Dae-jung (1924-2009, president 1998-2003) won the presidential election, marking the first election of an opposition-party candidate as well as the first win by a candidate from the Jeolla region. Although the Asian Financial Crisis (called the IMF Crisis in Korea because of a $58 billion bailout package from the IMF) was Kim’s top priority, he soon also followed through with a process of engagement with North Korea (named the Sunshine Policy, based on Aesop’s fable, “The North Wind and the Sun”). Kim Dae-jung went to Pyongyang and met with North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, ushering in a new era of cooperation between the two Koreas and winning the 2000 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. Kim’s successor, Roh Moo-hyun (1946-2009, president 2003-2008) also continued the Sunshine Policy and met with Kim Jong Il in 2007 for a second Inter-Korea Summit. Roh was impeached in 2004 for illegal electioneering but was not removed from office.

President Lee Myung-bak (1941-, president 2008-2013), a longtime business leader and former mayor of Seoul, became the next president. He was credited with Korea’s quick recovery from the worldwide recession of 2007-2008, and also hosted the G20 summit in 2010. He was succeeded by Park Geun-hye (1952-, president 2013-2017), the eldest child of Park Chung-hee, who became the first female president of South Korea. She was impeached in 2016 and removed from office in 2017 on corruption-related charges. Moon Jae-in (1953- , president 2017-2022) was elected after Park’s removal. Moon has met with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un three times, including once with then-US President Donald Trump. Korea was touted for its early success in halting the spread of COVID-19 through large-scale testing and tracing to identify positive cases for treatment. Koreans often wore masks in public even before COVID and were quick to adopt restrictions on gatherings to avoid massive lockdowns.

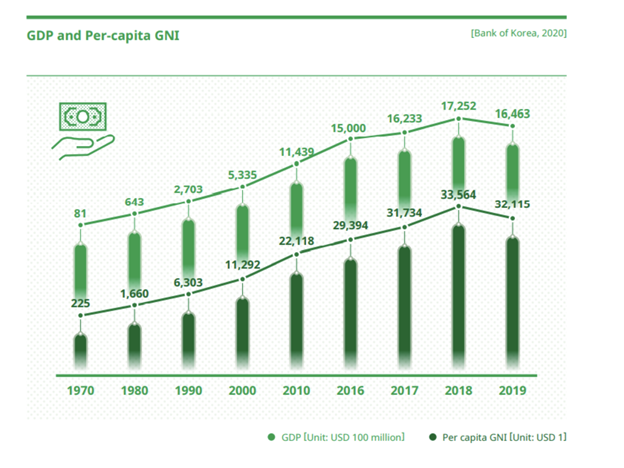

Figure 2 shows South Korea’s gross domestic product (GDP) in units of $100 million by decade from 1970 to 2010, and for years 2016-2019.We see remarkable growth through 2010, and continued growth in most years. According to the World Bank, the GDP was $1.631 trillion in 2020,[15] down only slightly from the 2019 figure of $1.6463 trillion despite the economic costs of the COVID-19 crisis. Figure 2 also shows the gross national income (GNI) per capita. According to the Bank of Korea, the per-capita GNI for 2020 was $31,881, down slightly from 2019, but this is not surprising given the worldwide pandemic. Korea is considered to be about the 10th largest economy in the world, with some calculations putting it even higher. South Korea was invited to the 2021 G7 Summit in recognition of its economic and democratic strength.

Fig. 2: South Korean GDP and Per-capita GNI

Source: Korea.net [16]

Fig. 3: South Korean Exports

| Rank | Export product | Export amount in US$ | Change since 2020 |

| 1 | Integrated circuits, micro-assemblies (semi-conductors) | $109,297,611,000 | +31.9% |

| 2 | Automobiles | $44,318,347,000 | +24.4% |

| 3 | Processed petroleum oils | $37,024,032,000 | +59.8% |

| 4 | Phone devices including smartphones | $21,992,020,000 | +22.4% |

| 5 | Automobile parts, accessories | $19,266,175,000 | +22.2% |

| 6 | Ships | $16,765,070,000 | +1.4% |

| 7 | Computer parts, accessories | $15,178,384,000 | +14.3% |

| 8 | Unrecorded sound media | $13,704,313,000 | +28.1% |

| 9 | Machinery to make semi-conductors | $9,275,360,000 | +10.3% |

| 10 | Electric storage batteries | $8,672,489,000 | +15.5% |

| 13 | K-beauty | $7,663,204,000 | +25.3% |

Fig. 4: Export Shipment Pier and Dock of Hyundai Motor’s Ulsan Factory

Source: Korea.net[20]

- 15. 2021 GDP is from the World Bank, “GDP (Current US$) – Korea, Rep,” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=KR, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 16.Korean Ministry of Cultural, Sports, and Tourism and the Korean Culture and Information Service, “The Korean Economy – the Miracle on the Hangang River,” Korea.net,

- 17. Oh Seok-Min, “(2nd LD) S. Korea Logs Record High Exports, Largest Ever Trade Deficit in 2022,” Yonhap News Agency (January 1, 2023), https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20230101001452320, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 18. Yonhap, “S. Korean Shipbuilders Rank 2nd in New Global Orders This Year,” (December 29, 2022), https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20221229000900320, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 19. Yonhap, “S. Korea’s Content Industry Exports Hit All-Time High in 2021,” (January 4, 2023), https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20230104006900315, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 20.Korea.net, https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/Economy/The-Miracle-on-The-Hangang, accessed February 20, 2023.

Most people in America have probably heard of BTS and Squid Game. BTS had four sold-out concerts in Los Angeles in November-December 2021, filling 50,000 seats each night. BTS’ label, Hybe (formerly Big Hit), has 63 million followers on YouTube. Their recent awards include 2021 American Music Awards (AMA) Artist of the Year, Favorite Pop Duo or Group, and Favorite Pop Song for “Butter,” their second English-language song. But as K-pop fans know, there are many groups as well as individual artists in many

genres encompassing pop, hip-hop, R&B, and more.

Figure 4: BTS

Source: Korea.net[21]

BTS, Parasite, and Squid Game are examples of the success of the Korean Wave, encompassing K-pop, Korean films, dramas, food, fashion, beauty, webtoons, sports (such as taekwondo), e-sports, and more. But the Korean Wave (also known as Hallyu) did not develop overnight. The term Soft Power was coined by Joseph Nye in the late 1980s and refers to “the use of positive attraction and persuasion to achieve foreign policy objectives.”[24] In the South Korean context, it means the way in which Korean popular culture has elevated the image of Korea around the world, and of course, the resulting boost to the Korean economy as more and more people learn about Korea and experience Korean culture for themselves, even learning the Korean language and traveling to Korea to visit, study, or work.

The South Korean government has successfully used Soft Power and public diplomacy to showcase all that Korea has to offer to the world, partnering with artists, companies, and worldwide fans to show how far Korea has come in the past several decades. In 2019, the Soft Power 30 Index ranked Korea 23rd for Soft Power. With the success of Parasite, BTS, as well as Netflix dramas such as Squid Game, South Korea is sure to rise in the next set of rankings.[25]

- 21.Korea.net, https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/Culture-and-the-Arts/Hallyu, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 22.Ryan General, “Leaked Data Reveals ‘Squid Game’ Has Made Netflix Nearly $900 Million, Over 42 Times Its Original Cost,” Yahoo! NextShark (October 18, 2021), https://www.yahoo.com/now/leaked-data-reveals-squid-game-173600577.html, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 23.Kevin Polowy, “’Parasite’: Bong Joon Ho Reveals Surprising Double-meaning Behind the Title of 2019’s Most Buzzed-about Film,” Yahoo! Entertainment, February 9, 2020, https://www.yahoo.com/now/parasite-movie-title-meaning-140024450.html, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 24.Soft Power 30 Index, https://softpower30.com/what-is-soft-power/, accessed February 20, 2023.

- 25.[1] Soft Power 30 Index, https://softpower30.com/country/south-korea/, accessed February 20, 2023.

South Korea is an economic and democratic success story, but as we have seen here, it was achieved through decades of struggle. The government spearheaded economic development in partnership with visionary corporations, but it would not have been possible without the sacrifices of countless workers. Today, South Korea is one of the most democratic countries in the world, but that also came through decades of struggle by students, labor groups, and many other segments of civil society. Both struggles were also hindered by Cold War tensions that vilified labor or political activism as anti-capitalist and pro-communist. Nonetheless, South Korea has come very far in the decades since the Korean War.

What might happen in the next two decades? As the South Korean economy continues to grow, perhaps there will be renewed attention on diversity, inclusion, and equity of people who are marginalized within Korea. And from what we have seen of recent trends, perhaps South Korea will also rise as a global leader in alleviating global health crises and fighting climate change. And of course, we expect to see lots more of Korean popular culture.

Ecker, Richard E. Korean Battle Chronology. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010, Reproduced on http://www.koreanwar-educator.org/topics/casualties/ecker/index.htm.

Eckert, Carter, Ki-baik Lee, Young Ick Lew, Michael Robinson, and Edward W. Wagner. Korea Old and New: A History. Seoul: Ilchokak Publishers for Korea Institute, Harvard University, 1991.

The Economist. “The World’s Most, and Least, Democratic Countries in 2022,” February 1, 2023. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/02/01/the-worlds-most-and-least-democratic-countries-in-2022.

General, Ryan. “Leaked Data Reveals ‘Squid Game’ Has Made Netflix Nealry $900 Million, Over 42 Times Its Original Cost.” Yahoo! NextShark, October 18, 2021. https://www.yahoo.com/now/leaked-data-reveals-squid-game-173600577.html.

Halloran, Richard Halloran. “Korea’s Vietnam Troops Cost U.S. $1 Billion.” The New York Times, September 13, 1970. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/koreas-vietnam-troops-cost-us-1billion.html.

Hankyoreh. “S. Korea Now Ranks World’s 10th Biggest Economy,” April 22, 2021. https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_business/992192.html.

Hwang, Kyung Moon. A History of Korea, third edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

Jo, Mi-Hyun. “S. Korea’s GNI per capital falls in 2022 on foreign exchange fluctuation.” The Korea Economic Daily, January 18, 2023, https://www.kedglobal.com/economy/newsView/ked202301180012.

Kim, Yon-se. “Korea to Rank 12th among G-20 Nations in 2022 Growth: OECD.” The Korea Herald, September 26, 2022. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220926000750.

Korea.net. BTS image. https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/Culture-and-the-Arts/Hallyu.

Korea.net. “Transition to a Democracy and Transformation into an Economic Powerhouse.” https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/History/Transition-Democracy-Transformation-Economic-Powerhouse.

Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism, and the Korean Culture and Information Service. “The Korean Economy – the Miracle on the Hangang River. https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/Economy/The-Miracle-on-The-Hangang.

Lee, Tae-hoon. “Gwangju Movement Bitter Turning Point for Democracy.” The Korea Times, May 17, 2010. https://koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2010/05/113_66017.html?utm_source=gonw.

The May 18 Memorial Foundation. http://eng.518.org.

Oh Seok-Min. “(2nd LD) S. Korea Logs Record High Exports, Largest Ever Trade Deficit in 2022.” Yonhap News Agency, January 1, 2023. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20230101001452320.

Polowy, Kevin. “’Parasite’: Bong Joon Ho Reveals Surprising Double-meaning Behind the Title of 2019’s Most Buzzed-about Film. Yahoo! Entertainment, February 9, 2020. https://www.yahoo.com/now/parasite-movie-title-meaning-140024450.html.

Soft Power 30 Index. https://softpower30.com/what-is-soft-power/.

Statistia. “Most Valuable Brands Worldwide in 2022,” https://www.statista.com/statistics/264875/brand-value-of-the-25-most-valuable-brands/.

Statistia. “Revenue of Leading Affiliates of Samsung Group as Percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in South Korea from 2017 to 2021.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/1314374/south-korea-samsung-groups-revenue-as-a-share-of-gdp/.

World Bank. “GDP (Current US$) – Korea, Rep.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=KR.

Yonhap. “S. Korean Shipbuilders Rank 2nd in New Global Orders This Year,” December 29, 2022. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20221229000900320.

Yonhap. “S. Korea’s Content Industry Exports Hit All-Time High in 2021,” January 4, 2023. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20230104006900315.

Jennifer Jung-Kim, PhD

UCLA Lecturer